We are not truly upright, we are only on our way to becoming upright. This is a metaphysical consideration. One of the jobs of a Rolfer is to speed that process along. -Ida Rolf

| Contents: |

1) 2-minute video showing what Rolfing looks like

Some detailed overviews of the sessions, including video summaries, are at alanrichardson-rolfing.com.br/en_gb/the-rolfing-series. See also a series of 30-second time-lapse videos demonstrating every session here, and on Youtube.

2) 9-minute video showing the concepts of Rolfing

excerpts from the excellent Strolling Under The Skin)

The Process

First, I don’t actually do Rolfing and am not yet certified by the IASI; see explanation.

Structural Integration (S.I.) is a system of treating the body’s entire structure, over a series of (up to) 10 sessions of 90 minutes each. You don’t have to commit to ten — many people just try the first session, or sessions #1-3. This “recipe” for treating the entire body was first developed almost 70 years ago by a biochemist named Ida Rolf, and has been refined continually by subsequent practitioners and researchers. Rather than making it up on a case-by-case basis, like with many kinds of massage where I’m treating one particular symptom (e.g. “my shoulders hurt today”), what the client receives is a time-tested scientific approach following prescribed choreography and specific long-term goals.

While no RMT can guarantee any results, in my experience almost all clients experience lasting, positive change within 3 sessions. Why 3? Three reasons. Firstly and most simply, it can take more than one visit before I understand what style of bodywork feels best for you, and before you can know the range of what I have to offer. Session #1 is “meet-and-greet” for the therapeutic relationship, and sometimes a bit of trial-and-error. By Session #2 you know how you felt after the first, and what to ask me for, and can more readily relax into receiving the process. By #3 we will have begun to establish a routine.

Three sessions allows me to approach your body in a graduated multi-level fashion, often starting with indirect myofascial or Swedish, then diving into deep-tissue massage, and finally arriving at the depth of Rolf’s direct myofascial. Thirdly, if you’ve requested the standard S.I. protocol, then 3 sessions is necessary to treat the whole body’s “superficial” fascia (following which we would begin addressing the “core” layers).

See descriptions of the 10 Rolfing sessions at the following websites:

overview:

more detail:

table:

What it feels like, and what you might feel after

It is different from massage in many ways — different style of contact, different intent, different mood… Many practitioners don’t even come from a massage background, but rather physiotherapy and osteopathy.

Unlike spa massage, most of the time you’ll be lying face-up, on your side, or sitting up. You keep your underwear on, though you’ll be draped with a sheet and blanket for warmth and comfort. Because the touch must be so slow — I have to concentrate more than in massage, and the receiver needs to focus her awareness to best internalize the sensations — the sessions can be meditative and quiet.

Techniques can include manually stretching tendons and entire muscles; contracting and relaxing muscles during stretches; pinning or moving muscles during lengthening; and sliding the superficial fascia between the muscles and the skin. There are two very different styles of myofascial release, referred to as direct vs. indirect techniques.

Movements are slow and deliberate. There is no pain — at least, not the way I do it! The key is taking it slow, warming everything up first. My sessions are “about” 90 minutes because my hands follow the needs of the body, not the dictates of the clock. As Rolf would say, “it’s not how deep you go; it’s how you go deep.”

Unlike regular massage, the rhythm can seem choppy. In relaxation massage, there’s continuous contact and a soothing flow; in S.I. the practitioner might spend 10 minutes on one part of your body and then pause, giving you a chance to breathe into the new sensations, before moving on to another part. It also includes some movement therapy; you will be standing up and walking around the room a couple times, to feel the changes in your limbs and joints, and some of the work will be done with you sitting on a stool.

One word best describes this style: intense. Nothing will hurt, but the way muscles and other layers are gently compressed and lengthened can feel “deep.” It is only uncomfortable to the extent that you are holding stress in your body. The key to avoid pain is taking it slow. I’ll check with you regularly to make sure it’s not too much pressure. It’s not the same kind of pressure used in standard deep-tissue massage or trigger-point therapy, but your body will feel more “worked-over.”

Most people feel interesting sensations after a treatment. Personally, after receiving one I’m energized and just want to move; after 90 minutes of having my muscles squeezed and slid around, my body just wants to walk, run, stretch. When I’m in bed that night, my body feels restless and alive, as my nervous system processes the new input. Sometimes people are a little tender the next day, but it’s a loose soreness, not a tight constricting one.

“One discovers by breathing that one had stopped breathing. One only discovers one’s stopped breath when one takes the next breath.” — Hélène Cixous, Hyperdream

If you’re thinking of taking a few sessions (3, 7, or all 10), I advise keeping a journal to chart your feelings and realizations before, during, and after. How does it feel to reside in your body? Where is your spirit at? What’s your emotional balance? You might find the changes to be as profound as I did; see My story: how I came to Rolfing.

How my work differs from “Rolfing”

First, the amount of training. Certified Rolfers take an intense, multi-month program, in what is probably the most detailed and thorough massage education there is. It’s only offered at a few cities around the world, and at limited times. While I’ve learned Rolfing-style massage from many teachers, I’m only certified in MIPA.

Rolfing™ and Rolfer® are trademarked names which can refer only to graduates of one specific program. “Structural Integration” is not trademarked, and names (“Rolf”) can not be registered.

Having said that, I adhere as close as I can to the method taught by Dr. Rolf, as I’ve experienced it from her students. What I’ve learned is only slightly modified from her 10-session protocol, but through my teachers’ own perspectives. While the workshops led by Craig Mollins and Barry Jenings (among my other teachers) were a reflection partly of their own personal approaches, I’ve also received personal mentorship from and studied the books by Dr. Edward Maupin, one of Rolf’s very first students. In fact, Ed is the last remaining first-generation Rolfer, Emeritus of the Rolf Institute, and founded the International Professional School of Bodywork. He was the first one to write a Rolfing textbook, has been kind enough to host me for private study sessions at his home in San Diego, and I help manage sales of and updates to his Structural Integration books — this is as close to the source of original Rolfing as I can get!

History of Rolfing

Myofascial release was first described by the founder of osteopathy, Andrew Still, in the early 1900s when it was called “fascial twist.” Physiotherapist Elizabeth Dicke later taught this technique as “Connective Tissue Massage,” which aimed to stretch the superficial fascia. The most focused study of myofascial techniques was by Dr. Ida Rolf in the mid-1900s, who applied her doctoral study of biochemistry to understand the structures of the body and learn how to help Westerners achieve the fluid grace of yoga poses. Rolf theorized that restrictions in fascia prevent muscles from functioning in concert with one another and affect movement and posture. The system she termed Structural Integration, which later become known simply as Rolfing, freed these fascial layers by manually separating and lengthening the fibers, softening the ground substance, and activating a release in the Central Nervous System. “Myofascial” was coined by physician Janet Travell in the 1940s in reference to myofascial trigger points, or muscle knots. The term “myofascial release” is credited to Rolfer Robert Ward in the 1960s and popularized by physiotherapist John Barnes in 1970s.

During these years myofascial therapy was only taught privately by osteopaths, physiotherapists, and Rolfers — who insisted on it remaining an oral tradition, only taught in person. It wasn’t until the 2000s that these theories were introduced to the public via books and videos, first by Art Riggs (Deep Tissue Massage, 2002), Michael Stanborough (Direct Release Myofascial Technique, 2004), and Edward Maupin (Dynamic Relation to Gravity, 2005), with an earlier theoretical overview by Tom Myers (Anatomy Trains, 2001). The field is now emerging as an independent field of inquiry — the world’s first International Fascia Research Conference was only held in 2007. S.I. is now taught in Canada by a small handful of second- and third-generation Rolfers (of whom my preferred style is Craig Mollins’ “MIPA” work). Sadly, there aren’t any Rolfers in Niagara Falls or St. Catharines, the closest being Toronto and Buffalo.

Structural Integration is easily the most scientifically-methodical form of massage. It was developed by a researcher with a PhD, with conceptual input from a nuclear physicist with a PhD (Moshe Feldenkrais, see more), and refined over many decades by later practitioners. The end result of this extensive research was a 10-session “protocol” carefully designed to be the most effective means of restoring balance and lightness to the body.

Why is this not more well-known?

As clients receive an S.I. session and feel its effectiveness, I’m often asked: why don’t more people practice this? For years I would simply shake my head and sigh, “I don’t know.” After much reflection and chats with my teachers, some ideas come to mind.

First, Rolfing is not a specific way of treating the body, but a philosophy of the body and the consciousness within it. It is not a technique, but rather an awareness of relationships. We don’t look at local symptoms and seek to fix their causes, but rather we try to grasp the relationships that exist in whole systems — the gestalt in which the whole is more than the sum of its parts. S.I. is not something that can be taught in a weekend course!

This approach requires intuition and years of experience. When I would learn other modalities, other massage techniques, I’d take a weekend course, practice it for a week, and then think “OK, I’ve got it.” But the more I practice Rolf’s method, the more infinite and deep it feels.

As Rosemary Feitis put it in her introduction to Rolfing and Physical Reality, “Rolfing is essentially an experiential art: nonverbal, even noncognitive.” She expands on this:

The ability to enter into other realities is called intuition. It is a faculty that is nourished by use, by the feedback of experience. … It can seem magical, like second sight. In reality, it is the product of time and experience, attention and work, and, of course, ability. This faculty is present in most Rolfers who have been practicing for some years. The magic lies in [Rolf’s] creation of a technique that allows practitioners to develop their own intuition and bring it to the service of others.

We are looking at the entire structure of a body and its nature as a physical expression of a cumulative lifetime of motions and emotions — the way we learned to stand as a toddler, that swing we fell off at age 5, those sports from age 15, that car accident at age 20, that heartbreak at age 25, that first childbirth at age 30, that work stress at age 40, that divorce at age 50 — it’s all reflected in both our energetic and our physical selves. When the client comes to the Rolfer and says “help me stand up straighter,” those previous motions and emotions are reflected in their present experience.

Rolfers also tend to not be good promoters of their work. Chiropractic, for example, was founded by a one-time salesman, and chiropractors have done an excellent job of achieving recognition by insurance companies, partly due to their excellent group cohesion, marketing ability, and simple explanations of both illness (subluxation) and their solutions to it (spinal adjustment). By contrast, Rolfers tend to be highly individualistic, creative people who are non-conformers and provide only complex nuanced answers. These qualities do not lend themselves to effective promotion.

S.I. also tends to attract a more rarified clientele. Rather than offering quick simple solutions which require only a 15-minute office visit to fix local symptoms, Rolfing requires a long-term commitment of time and a willingness to embark on a path of self-discovery to explore and resolve global causes (that swing fall from age 5, those sports from age 15, etc.)

Finally, the skill required of, and teachability of, Rolfing is unlike any other bodywork modality. Other modalities tend to offer specific easily-comprehended techniques, like “touch this muscle in this fashion and then move the joint in that direction.” By contrast, the longer one studies S.I. the more it can seem mysterious and deeper, infinite. The practitioner is not palpating for local easily-definable phenomena like knots, trigger points, adhesions, etc., but rather is sensing distant holding patterns, subtle compensations, areas of detached subjective awareness, and other intangibles. The Rolfer has in mind not a set of prescribed techniques, but amorphous goals which can be reached in a variety of ways and depend on the practitioner’s lengthy experience, skill, and intuition.

About Myofascial Integration Posture Alignment (MIPA)

My certification comes by way of a method called “Myofascial Integration — Posture Alignment” (see background) by Craig Mollins. Myofascial just means, your body’s muscles and the things that hold them in place. MIPA integrates these structures to align your posture, which helps free you from the various pulls of gravity that affect you as you move and work throughout your day. While I’ve taken mentorship sessions with Dr. Ed Maupin, the last remaining practitioner from Rolf’s original cohort and the author of its only textbook, my style is still closer to Craig’s than Ed’s.

MIPA bodywork is a uniquely effective way of healing chronic pain, or bringing you a more natural posture, or just making your body feel taller, lighter, and looser. The touch is done very slow, with minimal lotion, and at a deep-but-comfortable pressure, to gently lengthen areas of tightness. This can give you a significant sense of “release,” both in your physical body and in your emotional/mental state of relaxation.

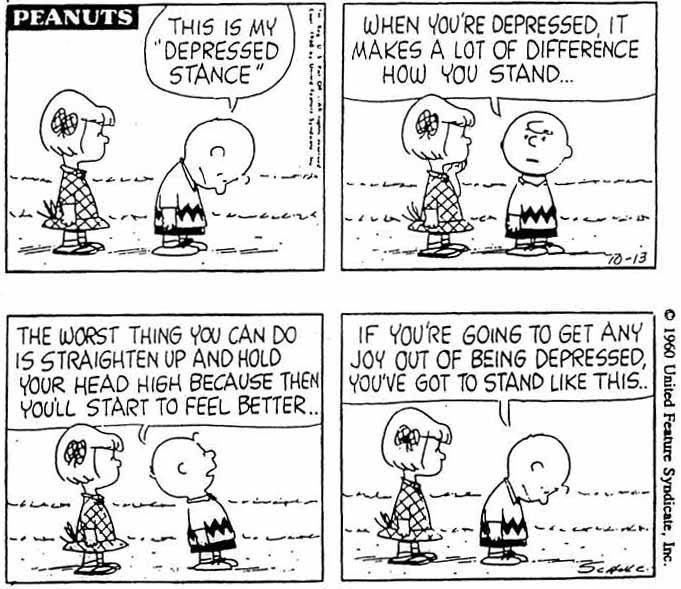

Mood affects posture: when we’re sad, we slump or go into the full curl of fetal position. Conversely, posture can affect mood. Rolfing/MIPA lengthens the body, brings the shoulders back and the head up, and the spirit lightens as well:

Background of MIPA

Craig Mollins’ MIPA is a descendant of the manual therapy founded by Rolf many decades ago, which has been refined over the years. As our understanding of fascial science evolves and our experimental tools improve, each new generation of Rolfers has built upon her insights with contemporary research — creating what I think is the single most effective form of bodywork. Rolf was unique in many ways: she was the first manual therapist to really treat the body as a single holistic system, she applied scientific methodology to create a logically-ordered “recipe” to treat that system, and she refined a form of manual contact which most effectively lengthens and re-educates the body’s soft-tissue structures.

RMT students are often taught to treat symptoms. If you find a trigger point, press on it until it goes away – problem solved! A more holistic approach sees local problems as but indicators of another issue, one which might not even be discernible in orthopedic assessment. Symptoms merely point to something larger. After working the body as a unified organism, treating the entire structure, local issues usually go away on their own. Nothing makes one feel looser and lighter, in body and spirit, than a series of Rolfing-style treatments.

Craig has modified and refined this approach over his own 3 decades of practice and through his unique perspective: Buddhist mindfulness. Fascial work requires quiet intuition. The therapist calms her mind and opens her heart. She meditates on, “what does it feel like to inhabit this other’s body?” When we focus our awareness, when we disengage the brain and engage the senses, we can tune in to a client in a way that we can’t when we’re thinking, diagnosing, assessing.

Fellow RMTs, take a class from Craig when you can. His teaching methods are excellent: he keeps everyone focused, the class environment attentive, and idle chat to a minimum. His explanations are precise, the demonstrations clear, and his hand-out manuals are thorough. Most important, he participates and engages with all students during sessions, attentive to how they are practicing and quick to offer helpful feedback. While all instructors should do this, surprisingly few really do. No time is wasted in his courses, and at the end of the day you know you’ve learned as much as you can.

Clients comment on how “present” I seem and how effective it then feels. This is a credit both to the Rolfing style of bodywork, but also to Craig: cultivating awareness and empathy in his students is one of his most valuable contributions. See Craig’s mipawork.com, or read more about my own philosophy of treating fascia.